In the final few weeks of Spring 2020, I opened the front door one glorious morning and was treated to the tranquility of an American Goldfinch resting atop our planter. Truly a delight to see. So, I decided to pay it forward. I’ve been broken Like a lonely dream Looking for a mind to enter, But I follow the footsteps of love Through the crowded halls of hate. I’m a patient man, From every act of unkindness, One day, I will escape-- Meet me at dawn, We’ll gaze at yellow birds, Our affection will be new Like the first day of creation. ~ by Uriah Hamilton

1 Comment

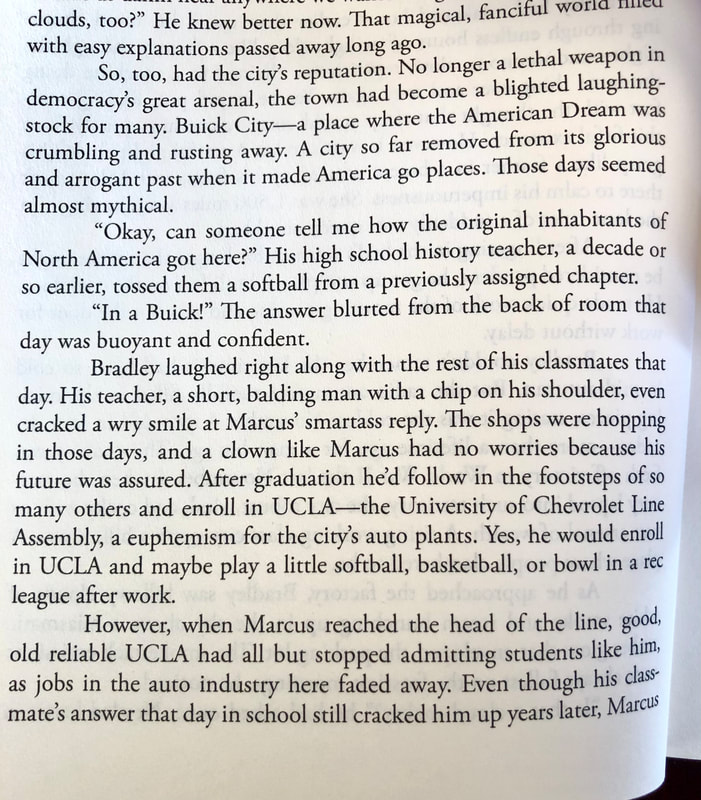

Kevin Roose's terrific interview on today's Fresh Air (March 16, 2021) about his new book, Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation, spoke to the transformation that occurred in the automotive industry and the effect on later generations in factory towns like Flint.

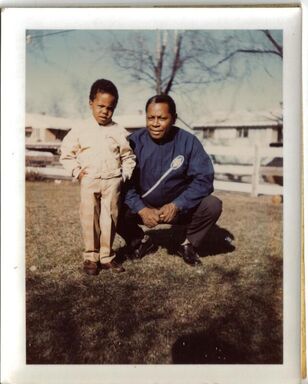

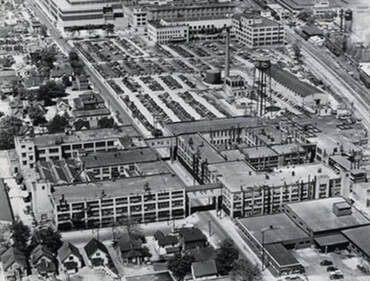

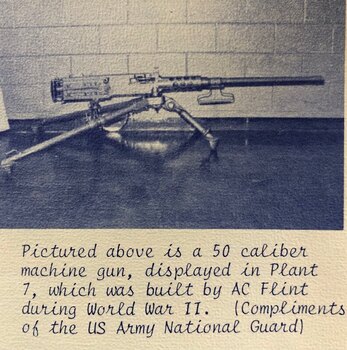

Roose said: "We need to prepare for the possibility that a lot of people are going to fall through the cracks of this technological transformation. It's happened during every technological transformation we've ever had, and it's going to happen this time. And in fact, it already is happening. ... [A] lot of the people who went through those technological transformations ... didn't have a good time. They weren't necessarily happier, or living better lives, or wealthier as a result of this new technology. ... Old jobs have been disappearing faster than new jobs have been created." This promise and peril of automation -- also known as "deindustrialization," from an earlier period -- is a theme in my novel Motown Man, which is set in the early 1990s in a fictionalized version of Flint. Bradley, the book's main character, is reminded of the plight of two individuals who fell "through the cracks" as industry automation, designed by electrical engineers like him, made certain jobs obsolete. Two excerpts:  Photo: Courtesy of CBS Photo: Courtesy of CBS Meghan Markle told Oprah during the CBS-televised interview that several members of the Royal Family discussed with Harry concerns over what the color of Archie’s skin would be. VIDEO CLIP Her comments struck a core theme in Motown Man. Abby, a main character in the novel, is faced with that issue when her father questions what his daughter's marriage to Bradley will mean for future generations. Read the Motown Man excerpt below: [Abby's father] focused instead on the future grandchildren. No doubt they would be black even if they looked white. They would be black and forever marked with that indefinable quality of separateness. And if they came out with permanently brown skin, which was quite likely because of Bradley's complexion, there could be no faking it for the white grandparents pushing the stroller in the park.  I awoke the morning of Feb. 21 thinking how I needed to get up to let Max out. But instead of the tick, tick, ticking of his small claws against the hardwood floor as he paced about or the occasional bark to warn me that I had better get moving (actually, he hadn’t barked in months), there was only silence. A day earlier, Max took his final ride to the vet. Unlike previous trips, he didn’t make a fuss. He rested peacefully against my wife's bosom. Afterwards, Wanda and I returned home alone. The blanket used to keep him cozy and comfortable for the ride over now folded flat and as empty as our hearts. My 24-year-old son, Jonathan, had already said goodbye in his own way. Black mystery, crime, and suspense fiction of the 20th century I've had this book for sometime but it got buried in my stacks. I finally pulled it off the shelf and jumped in. It's a terrific anthology, with an interesting variety of short stories and novel excerpts. It also introduced me to a number of writers I had never heard of. I particularly like the stories in the section titled "Sistahs in Crime," especially Tell Me Moore by Aya de Leon and Night Songs by Penny Mickelbury. Also enjoyed the section "Spooks at the Door," which included novel excerpts from The Man Who Cried I Am by John A. Williams and The Spook Who Sat by the Door by Sam Greenlee. Both novels are set in the late '60s and with themes of Black nationalism that characterized the period. After reading Greenlee's piece, I bought and read the novel. It's a good read, too. (I haven't been able to find a copy of Williams' novel.) I don't read much crime and mystery fiction, with the exception of Walter Mosley (who's also represented in the anthology). This book delivers on the genre, wrapped in the richness and earthiness of Black culture across different periods of the 20th century.  My father and me years before I wanted to be "grown." My father and me years before I wanted to be "grown." I said once, in the presence of my father, how I wished to be older. I was, at the time, 12 or 13, maybe 14. The comment wasn’t necessarily directed at him but more so at the rest of the world. Being older – “grown,” that is – meant freedom unlimited and command. I’m sure that’s what I thought. Whether he was a contributor to the frustration I felt then didn’t matter. The audible statement had been broadcast for anyone within earshot to hear. My wish was now part of the public domain – like a tweet to a tiny circle of followers, posted with the hashtags #whoslistening #freeme #cosmiccars – and an invitation or plea, of sorts, for reaction. My father responded almost reflexively. “Don’t wish your life away,” he sighed, as if thinking aloud and perhaps even recalling a much younger version of himself. The depths of a father’s few words. If I were 12 or 13, maybe 14, he would have been in his mid-50s – about my age now – and retired from AC Spark Plug (earlier than planned due to a medical disability). He might have felt the finish line was now visible on the horizon, however distant. A constant presence like the inescapable gaze of a female portrait whose painted eyes appear to follow you across the room. Possibly in that very moment, the idea of a personal expiration date was too imaginable to ignore. (How many more seasons left on the calendar?) Take my advice, he said without saying, make the most of your time where you are. Enjoy the beauty, the challenge and the magnificence of the moment if you can. Contained within his prescient advice – “Don’t wish your life away” – was also a quiet, respectful appeal: “And don’t wish my life away.” For, the older I got the older he got. He wasn’t ready to breach the horizon according to someone’s else watch. To the extent possible, his time remaining belonged to him. He would live another 30 years. (c) Bob Campbell/bobcampbellwrites.com  Driving home on July 1 at 9:30 p.m. after an evening session of radiation (delayed a full day from my usual morning appointment due to an equipment malfunction), the sun had recently set, replaced by a waxing gibbous moon. The temperature had cooled about 10 degrees or so from the daytime high in the low 90s. Traffic light, the two-mile drive along the surface streets from the treatment center to I-75 was gratifying. The car windows down, sunroof open, Real Jazz on SiriusXM (On Green Dolphin Street to be followed by A Love Supreme), amateur fireworks exploding silently in the distant sky.  This 1997 column for the Lexington Herald-Leader landed me a televised interview on ESPN and several interviews with sports radio shows that served SEC country. It's about when the University of Kentucky was then-considering hiring Tubby Smith to be its first black basketball coach. There was a lot of hand-wringing at the time about whether UK basketball was ready for a black head coach. Fellow journalists seemed to particularly like the second sentence, which answered the questioned I posed in the first. I was also surprised by the degree of support received from UK fans. In support of the fundraising campaign to erect a statue of Rosie the Riveter, part of the Automobile Heritage Collection, at Flint's Bishop Airport, it was an honor to contribute a portion of my family's history to the effort. Mom's story is below.  Rose Holliday Campbell, born February 14, 1925, in Detroit and raised in Flint. After graduating from Flint Central High School in 1943, she went to work at AC Spark Plug on Industrial Avenue to help produce munitions for soldiers in World War II. She was a machine operator – considered a semi-skilled position – and quite possibly operated a lathe turning gun barrels or some other type of production machining operation. AC produced .50-caliber machine guns on Industrial and test fired the weapons in the basement. (Her mother, Rosa Holliday also worked at AC during WW II) Her husband, Clarence, was a U.S. Army staff sergeant and served in combat with the 92nd Infantry Division in Italy. After the war, Rose left AC to make room for the returning veterans and became an elevator operator at Citizens Bank’s headquarters in downtown Flint. Rose and Clarence, who returned to AC where he had been employed when the war began, raised six children. Married for 65 years, they are buried together at Great Lakes National Cemetery in Holly, Michigan. (c) 2020 Bob Campbell/bobcampbellwrites.com |

AuthorBob Campbell, an essayist and novelist, likes his bourbon neat. His debut novel, Motown Man, was published by Urban Farmhouse Press in November 2020. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed